What Modularity Really Means

The systemic principle that offsite has not fully adopted.

In everyday language, “modular” suggests flexibility, efficiency, or ease of assembly. But in systems theory, modularity has technical features that make it a powerful idea.

Modularity is a systemic principle: it describes the deliberate partitioning of a complex system into distinct components, each internally coherent, yet aligned through shared interface rules.1 These “design rules” specify how the parts fit together—physically, electronically, or procedurally—so that each can be developed independently but still function within the whole.

What makes this organization so powerful is not the parts themselves, but the interfaces that coordinate them. 2 A well-structured interface decouples the development of each module, enabling parallel innovation, specialization, and substitution. This is what allowed the computing industry to scale so explosively in the 1980s and 90s: once IBM published stable specifications for internal buses and peripheral slots, third-party firms could design CPUs, memory chips, and software without negotiating every connection. The result wasn’t just better parts — it was an entire ecosystem. Automotive platforms,3 aircraft assemblies,4 and even camera systems followed suit. In every case, the breakthrough was systemic clarity: modules existed, but modularity emerged only when interfaces stabilized.

In the contemporary world of architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC), this deeper definition of modularity is often misunderstood or ignored. Factories fabricate pods and panels, and projects are called “modular” because components are built offsite. But a major commonality of failed modular firms (Katerra, Crate, Hegg, etc.) is that each firm insists on controlling its own interface standard. They grew too dependent on a narrow list of bespoke Tier 2 suppliers. The supply chains grew too brittle; any break in the chain doomed the whole enterprise. Neglecting interfaces is not a technical flaw; it’s a strategic vulnerability that has already played out in high-profile collapses.

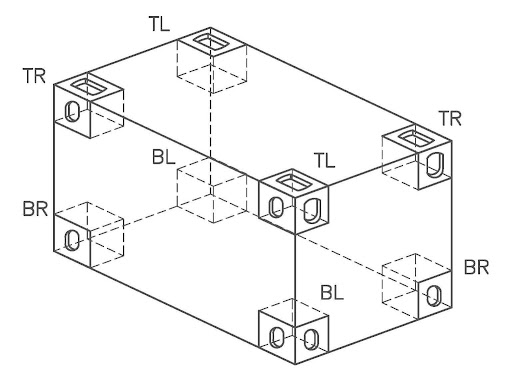

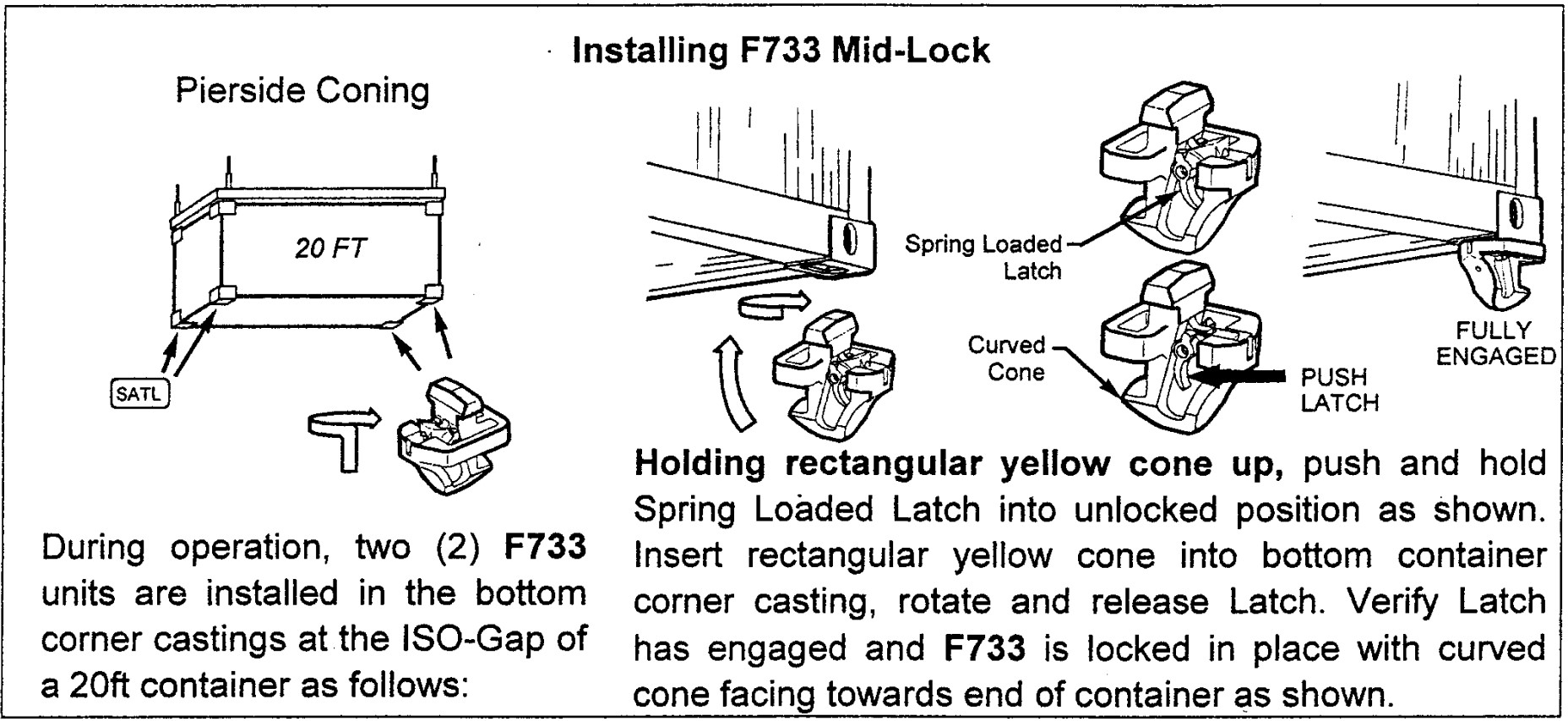

Image Credit(s): Peck & Hale 1996 catalog of ISO 1161 compliant shipping container twist lock mechanisms.

Without shared interface standards (functionally: without collaborative design rules) these parts remain bespoke. Each pod must be re-detailed, coordinated, inspected, and approved for every new project. Risk migrates into the seams. Transaction costs pile up. Innovation is stunted because nothing repeats cleanly.

The CTO Marketplace asserts that this is not an accident; it is the predictable outcome of an industry that builds modules without embracing modularity. The missing ingredient is the interface. Until the AEC industry develops and adopts shared physical, digital, and regulatory couplings, modular construction will remain locked in an Engineer-to-Order (ETO) mindset, never achieving the scale or speed seen in other modularized industries.

Interfaces are what transform a set of isolated products into a marketplace, because they make interoperability5 possible,6 and thus allow multiple suppliers to compete and collaborate without custom negotiation for every transaction. In industries from electronics to logistics, stable interface specifications have enabled buyers to mix and match components from different vendors, confident that they will connect and perform as expected. This predictability reduces technical risk and market friction. It opens the door for specialized producers to focus on what they do best, while integrators assemble complete systems from a broad, competitive field. Without such interoperability, there is no true market, only a series of one-off, closed supply chains.

This is why the CfOC has focused its early efforts on writing the interface standards that modular construction has long needed. Through our partnership with the International Code Council and ANSI accreditation, we are defining open-standard “design rules” for modular buildings — where value is exchanged, where scope is handed off, and where modules connect. Our goal is not just better products, but an open architecture for collaboration — one that others, anywhere, can build upon.

Related Links:

- Design Models CTO (Project Start Resources & Coordination Form)

- Modular Interoperability Standard (Research Roadmap)

- Baldwin & Clark, Design Rules, Volume 1: The Power of Modularity (2000). ↩︎

- Baldwin & Clark Design Rules: Volume 2: How Technology Shapes Organizations (2023) Chapter 13. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 474. “Modularity allows the parts of a system to be changed without affecting the whole… This capacity to change confers ‘option value’ on the system: the ability to defer decisions, adapt to new information, and innovate without disrupting existing operations.” ↩︎

- Timothy J. Sturgeon, “Modular Production Networks,” Industrial and Corporate Change (2002). ↩︎

- Jaswant Singh “The Role of ARINC Standards in Aircraft System Integration and Interoperability” (2024) ↩︎

- “Interoperability is a characteristic of a product or system to work with other products or systems.” (Wikipedia). See interfaces enabling interoperability in e commerce, data management, weaponry, etc. ↩︎

- Baldwin & Clark Design Rules: Volume 2 — How Technology Shapes Organizations (2023) Chapter 13. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 474.“Well-specified interfaces make it possible for different actors to innovate independently, coordinating only through the shared interface definition. The result is an expansion of the space of possible designs that can be realized without centralized control.” ↩︎